In the previous lesson, we learned about Go’s concurrency model. As goroutines are lightweight compared to OS threads, it is very common for a Go application to have thousands of goroutines running concurrently. Concurrency can speed up application significantly as well as help us write code with separation of concerns (SoC).

What is a goroutine?

We understood in theory that how goroutine works, but in code, what is it? Well, a goroutine is simply a function or method that is running in background concurrently with other goroutines. It’s not a function or method definition that determines if it is a goroutine, it is determined by how we call it.

Go provides a special keyword go to create a goroutine. When we call a function or a method with go prefix, that function or method executes in a goroutine. Let’s see a simple example.

package main

import "fmt"

func printHello() {

fmt.Println("Hello World!")

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("main execution started")

// call function

printHello()

fmt.Println("main execution stopped")

}

// main execution started

// Hello World!

// main execution stopped

In the above program, we created a function printHello which prints Hello World! to the console. In main function, we called printHello() like a normal function call and we got the desired result.

Now let’s create goroutine from the same printHello function.

package main

import "fmt"

func printHello() {

fmt.Println("Hello World!")

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("main execution started")

// create goroutine

go printHello()

fmt.Println("main execution stopped")

}

// main execution started

// main execution stopped

Well, as per goroutine syntax, we prefixed function call with go keyword and program executed well. It yielded the following result.

main execution started

main execution stopped

It is a bit strange that Hello World did not get printed. So what happened?

goroutines always run in the background. When a goroutine is executed, here, Go does not block the program execution, unlike normal function call as we have seen in the previous example. Instead, the control is returned immediately to the next line of code and any returned value from goroutine is ignored. But even then, why we can’t see the function output?By default, every Go standalone application creates one goroutine. This is known as the main goroutine that the main function operates on. In the above case, the main goroutine spawns another goroutine of printHello function, let’s call it printHello goroutine. Hence when we execute the above program, there are two goroutines running concurrently. As we saw in the earlier program, goroutines are scheduled cooperatively.

Hence when the main goroutine starts executing, go scheduler dot not pass control to the printHello goroutine until the main goroutine does not execute completely. Unfortunately, when the main goroutine is done with execution, the program terminates immediately and scheduler did not get time to schedule printHello goroutine. But as we know from other lessons, using blocking condition, we can pass control to other goroutines manually AKA telling the scheduler to schedule other available goroutines. Let’s use time.Sleep() call to do it.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func printHello() {

fmt.Println("Hello World!")

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("main execution started")

// create goroutine

go printHello()

// schedule another goroutine

time.Sleep(10 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("main execution stopped")

}

// main execution started

// Hello World!

// main execution stopped

We have modified program in such a way that before main goroutine pass control to the last line of code, we pass control to printHello goroutine using time.Sleep(10 * time.Millisecond) call. In this case, the main goroutine sleeps for 10 milli-seconds and won’t be scheduled again for another 10 milliseconds. Once printHello goroutine executes, it prints ‘Hello World!’ to the console and terminates, then the main goroutine is scheduled again (after 10 milliseconds) to execute the last line of code where stack pointer is. Hence the above program yields the following result.

main execution started

Hello World!

main execution stopped

If we add a sleep call inside the function which will tell goroutine to schedule another available goroutine, in this case, the main goroutine. But from the last lesson, we learned that only non-sleeping goroutines are considered for scheduling, main won’t be scheduled again for 10 milli-seconds while it’s sleeping.

Hence the main goroutine will print ‘main execution started’, spawning printHello goroutine but still actively running, then sleeping for 10 milli-seconds and passing control to printHello goroutine. printHello goroutine then will sleep for 1 milli-second telling the scheduler to schedule another goroutine but since there isn’t any available, waking up after 1 milli-second and printing ‘Hello World!’ and then dying. Then the main goroutine will wake up after a few milliseconds, printing ‘main execution stopped’ and exiting the program.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func printHello() {

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("Hello World!")

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("main execution started")

// create goroutine

go printHello()

// schedule another goroutine

time.Sleep(10 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("main execution stopped")

}

// main execution started

// Hello World!

// main execution stopped

Above program will still print the same result

main execution started

Hello World!

main execution stopped

What if, instead of 1 milli-second, printHello goroutine sleeps for 15 milliseconds.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func printHello() {

time.Sleep(15 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("Hello World!")

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("main execution started")

// create goroutine

go printHello()

// schedule another goroutine

time.Sleep(10 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("main execution stopped")

}

// main execution started

// main execution stopped

In that case, the main goroutine will be available to schedule for scheduler before printHello goroutine wakes up, which will also terminate the program immediately before scheduler had time to schedule printHello goroutine again. Hence it will yield below program

main execution started

main execution stopped

Working with multiple goroutines

As I said earlier, you can create as many goroutines as you can. Let’s define two simple functions, one prints characters of the string and another prints digit of the integer slice.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func getChars(s string) {

for _, c := range s {

fmt.Printf("%c ", c)

}

}

func getDigits(s []int) {

for _, d := range s {

fmt.Printf("%d ", d)

}

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("main execution started")

// getChars goroutine

go getChars("Hello")

// getDigits goroutine

go getDigits([]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5})

// schedule another goroutine

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("\nmain execution stopped")

}

// main execution started

// H e l l o 1 2 3 4 5

// main execution stopped

In the above program, we are creating 2 goroutines from 2 function calls in series. Then we are scheduling any of the two goroutines and which goroutines to schedule is determined by the scheduler. This will yield the following result

main execution started

H e l l o 1 2 3 4 5

main execution stopped

Above result again proves that goroutines are cooperatively scheduled. Let’s add another time.Sleep call in-between print operation in the function definition to tell the scheduler to schedule other available goroutines.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

var start time.Time

func init() {

start = time.Now()

}

func getChars(s string) {

for _, c := range s {

fmt.Printf("%c at time %v\n", c, time.Since(start))

time.Sleep(10 * time.Millisecond)

}

}

func getDigits(s []int) {

for _, d := range s {

fmt.Printf("%d at time %v\n", d, time.Since(start))

time.Sleep(30 * time.Millisecond)

}

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("main execution started at time", time.Since(start))

// getChars goroutine

go getChars("Hello")

// getDigits goroutine

go getDigits([]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5})

// schedule another goroutine

time.Sleep(200 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("\nmain execution stopped at time", time.Since(start))

}

// main execution started at time 0s

// H at time 0s

// 1 at time 0s

// e at time 10ms

// l at time 20ms

// l at time 30ms

// 2 at time 30ms

// o at time 40ms

// 3 at time 60ms

// 4 at time 90ms

// 5 at time 120ms

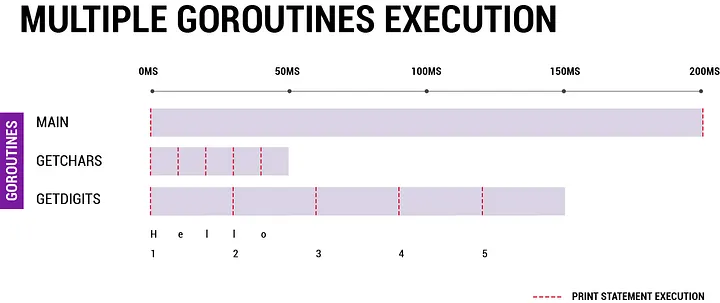

In the above program, we printed extra information to see when a print statement is executing since the time of execution of the program. In theory, the main goroutine will sleep for 200 milliseconds, hence all other goroutines must do their job in 200 milliseconds before it wakes up and kills the program. getChars goroutine will print 1 character and sleep for 10 milli-second, passing control to getDigits goroutine which will print a digit and sleeping for 3 milli-seconds passing control to getChars goroutine again when it wakes up. Since getChars goroutine can print and sleep multiple times, at least 2 times while other goroutines are sleeping, we are hoping to see more characters printed in succession than digits.

Below result is taken from running above program in Windows machine.

main execution started at time 0s

H at time 1.0012ms <-|

1 at time 1.0012ms | almost at the same time

e at time 11.0283ms <-|

l at time 21.0289ms | ~10ms apart

l at time 31.0416ms

2 at time 31.0416ms

o at time 42.0336ms

3 at time 61.0461ms <-|

4 at time 91.0647ms |

5 at time 121.0888ms | ~30ms apart

main execution stopped at time 200.3137ms | exiting after 200ms

We can see the pattern we talked about. This will be cleared to you once you see the program execution diagram. We will approximate that print command takes 1ms of CPU time, compared on the 200ms scale, that’s negligible.

Now we understood how to create goroutine and how to work with them. But using time.Sleep is just a hack to see the result. In production, we don’t know how much time a goroutine is going to take for the execution. Hence we can’t just add random sleep call in the main function. We want our goroutines to tell when they finished the execution. Also at this point, we don’t know how we can get data back from other goroutines or pass data to them, simply, communicate with them. This is where channels comes in. Let’s talk about them in the next lesson.

Anonymous goroutines

If an anonymous function can exist then anonymous goroutine can also exist. Please read Immediately invoked function from functions lesson to understand this section. Let’s modify our earlier example of printHello goroutine.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println("main execution started")

// create goroutine

go func() {

fmt.Println("Hello World!")

}()

// schedule another goroutine

time.Sleep(10 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("main execution stopped")

}

// main execution started

// Hello World!

// main execution stopped

The result is quite obvious as we defined the function and executed as goroutine in the same statement.

All goroutines are anonymous as we learned from

concurrencylesson as goroutine does not have an identity. But we are calling that in the sense that function from which it was created was anonymous.